I have been thinking lately about perception and judgement, and how these constructs manifest, especially in the arena of addiction. As you know by now if you’ve been following any of these entries, I am a recovering addict - I have accrued years of first-hand, intimate knowledge of the disease and affliction -yet I know that I am probably just as susceptible to ascribing negative stereotypes to people who regularly use or abuse illicit mind and mood altering substances. I think the stereotypes exist for a reason, because there is truth in the idea that yes, a lot of people who struggle with addiction are from lower socio-economic backgrounds. You know the kind. The family of 13 with the young woman pushing 4 kids down the street in a twin stroller, dragging another kid by his collar to avoid getting hit by a street bicyclist while she struggles to get to the Cigarette Shopper to buy a carton of cigarettes using money she obtained by trading her snap benefits for cash. It’d be a fair wager that there probably is, or has been, some illicit drug use in her life. Or, for example, the guy camped out on the median strip with his cardboard sign and poor dog. Most likely a junkie, yes. And I don’t use that term lightly, either. I believe (and hope) one day the phrase “junky” will be weeded out of the parlance of the times, much like “retard” or “faggot” was years ago. The term “junky”, to me, is incredibly offensive. But alas, I am not here to be a social justice warrior or virtue signaler or whatever. I can take it, I’ve been called much worse in my day. As Bukowski once said “Those who escape Hell, however, never talk about it and nothing much bothers them after that.” So, you can call me a junky, just not the woman pushing the twin stroller or the poor guy on the median. They beat themselves up quite enough, trust me.

These stereotypes seem to perpetuate themselves I think because substance use disorder and mental illness are so inextricably linked. It is no coincidence a lot of “street people” - (the unhoused population) - one encounters are struggling with this dual diagnoses. However, I am here to tell you that addiction does not discriminate. I am sure many of you have heard this phrase ad infinitum (“it doesn’t matter if you’re on Park Avenue or Park Bench!”). It’s cliche as all hell for sure. But again, stereotypes and cliche’s exist because they are often formed from a germ of indisputable truth. Because these people are so visible in our society, it goes on to follow that logically it’s these types of people and these people alone that “have the problem” and “need help”. Which is the truth, but it is only one part of a much bigger truth, which is addiction comes in many different guises and affects every socioeconomic background and pedigree.

I was brought up relatively privileged I would have to say. I had everything I needed and wanted. No trauma to blame. Every advantage. For a long time I felt incredibly guilty about this fact. Why couldn’t I just have capitalized on this head start in life? Why am I the way I am? I spent years looking into my past like a tax-auditor, looking for things, events, people, episodes that I could directly attribute to my disease and the unmanageability of my life. These efforts were ultimately futile, and it started taking away from dealing with the issue head on. I could spend a thousand years looking for the why’s and just spin in figure-eights the entire time. I eventually came to the conclusion that my time was much better spent devoting my energies to figure out methods and discover tools that would help me stay away from the temptations of mood altering substances.

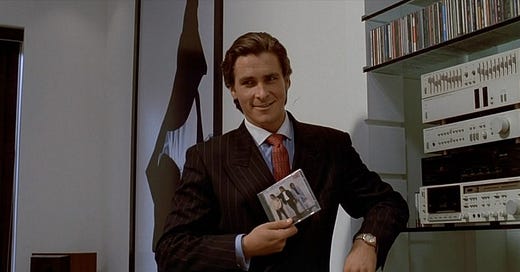

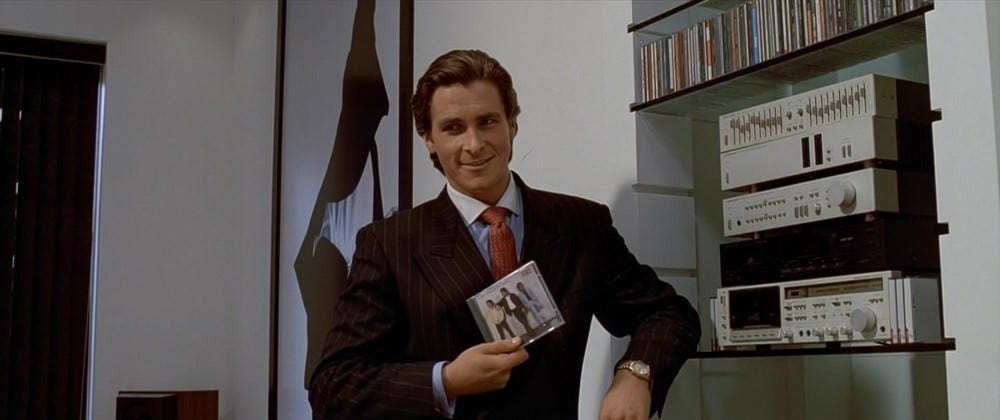

I have been a white-collar professional. I am university graduate. I have received promotions while using methamphetamine. I have been a loving husband, a doting father, a successful pre-med student, a kids basketball coach, all while in addiction. I have also been homeless, sleeping outdoors, and drinking out of people’s backyard hoses in the middle of the night to hydrate myself. I have proverbially been the guy on the median. Addiction will still fit in anywhere it can, it just tends to manifest itself more subtly if one has the means to afford their respective habit. I would say that for most of my life I was a functioning drug addict. It was because of that privilege and head start that I wasn’t on the streets sooner. I was somehow able to graduate from Northeastern University with honors while also taking care of a full time opioid habit. The more means and money one has at their disposal, the less threatening an addiction appears. If you’re a hedge-fund manager and your habit costs a few grand a week, then it’s just that, a habit. It’s not life threatening. Take the same addiction and flip the socioeconomics around…maybe that person doesn’t have 3k per week to spend on pharmaceutical grade heroin, so they are forced to buy fentanyl and become the modern leper of society. This is why addiction and alcoholism is so intertwined with the idea of class and a moral failing. We don’t see the well-off who struggle with addiction panhandling on the streets because their addiction costs them pennies on the dollar compared to the worse off person.

Recently, it came to my attention that a parent was concerned about the safety of one of my kids because I was in recovery. They said “you shouldn’t have to be forced to live with a parent who is an addict”. This, of course, made me start to think. Obviously, I was angry. My daughter has never seen me drunk or incapacitated or out of control due to mind altering substances. I take great pride in being a parent. Clearly, parenting from a place of sobriety is superior to parenting from a place of inebriation of any kind. But, I started to think about the judgements and perceptions that that parent had to have to think that because I struggle with addiction it automatically meant I was a toxic or dangerous person. They probably had thoughts of the household as being chaotic, with my wife and I yelling and at each other’s throats constantly…inanimate objects being thrown around the house, doors slamming, tears at every turn. This couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, in my active addiction, the domestics of the household moved like a well-oiled machine. Kids were picked up on time, teeth-brushing and pajamas started on time every night, meals were cooked with love. I had to work extra hard to convey this air of normalcy and okayness to make up for the ways I was slowly killing myself when no one was looking. It was a full-time job on top of a full-time job. Most of the time I have been in active addiction it has been under the radar. You wouldn’t know it unless you knew me very well.

For the privileged, the destruction of addiction often hides behind thick walls, luxury rehab centers, and polite euphemisms like “exhaustion,” “stress leave,” or “a brief stay down south.” But the pain is arguably just as real, just as corrosive. Money might buy more time, more privacy, even a more comfortable descent, but it can’t stop the spiritual rot that addiction brings. It erodes trust, devastates families, and hollows out identity with the same relentless force. In some ways, addiction among the well-to-do of society can be even more insidious; there’s more to lose, more denial, and more people willing to enable the illusion of control. A person can overdose in designer sheets with a 3,000 thread count, just as alone and lost as anyone else. And often, because society wraps their suffering in velvet, they die quietly — misunderstood, minimized, or worse, glamorized.

Addiction doesn’t give a damn who you are. It doesn’t care if you wear a Valentino suit or sleep under an overpass, if you’ve got a trust fund or food stamps. It’s an equal-opportunity destroyer… subtle, insidious, and patient. You could be the golden child or the fuck-up, a genius or a ghost. Addiction finds the cracks in all of us and slowly widens them. You’re still in there somewhere, screaming to get out and sometimes, if you’re lucky, if you’ve got a lifeline or just a little grace, you claw your way back out.